Fourth Sunday of Easter, Year B – April 26, 2015

Fourth Sunday of Easter, Year B – April 26, 2015

Tending flocks and herds is an important part of the Palestinian economy in biblical times. In the Old Testament, God is called the Shepherd of Israel who goes before the flock (Psalm 68:7), guides it (Psalm 23:3), leads it to food and water (Psalm 23:2), protects it (Psalm 23:4), and carries its young (Isaiah 40:11). Embedded in the living piety of believers, the metaphor brings out the fact that God shelters the entire people.

In Psalm 23, the author speaks of the Lord as his shepherd. The image of shepherd as host is also found in this beloved psalm. Shepherd and host are both images set against the background of the desert, where the protector of the sheep is also the protector of the desert traveller, offering hospitality and safety from enemies. The rod is a defensive weapon against wild animals, while the staff is a supportive instrument; they symbolize concern and loyalty.

The New Testament does not judge shepherds adversely. They know their sheep (John 10:3), seek lost sheep (Luke 15:4ff.), and hazard their lives for the flock (John 10:11-12). The shepherd is a figure for God himself (Luke 15:4ff.).

Confidence

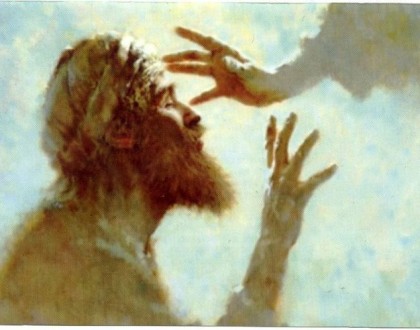

On the Fourth Sunday of Easter, traditionally called Good Shepherd Sunday, we encounter the Good Shepherd who is really the beautiful or noble shepherd [in the Greek text] who knows his flock intimately. Jesus knew shepherds and had much sympathy for their lot and he relied on one of his favourite metaphors to assure us that we can place our confidence in him. For those who heard Jesus claim this title for himself, it meant more than tenderness and compassion; there was the dramatic and startling degree of love so great that the shepherd is willing to lay down his life for his flock.

Unlike the hired hand, who works for pay, the good shepherd’s life is devoted to the sheep out of pure love. The sheep are far more than a responsibility to the good shepherd — who is also their owner. They are the object of the shepherd’s love and concern. Thus, the shepherd’s devotion to them is completely unselfish; the good shepherd is willing to die for the sheep rather than abandon them. To the hired hand, the sheep are merely a commodity, to be watched over only so they can provide wool and mutton.

The beauty of Jesus, our Good Shepherd, lies in the love with which he offers his life even unto death for each and every one of his sheep. In so doing, he establishes with each one a direct and personal relationship of intense love. Jesus’ beauty and nobility are revealed in his letting himself be loved by us. In Jesus we discover the Father and his Son who are shepherds who care for us, know us and even love us in our stubbornness, deafness and diffidence.

Sometimes, it seems that followers are expected to put the needs of the leader first. The people are the means to an end: the leader’s pleasure. Does it not often seem that shepherds are first, sheep last? The emphasis in today’s readings is on the sheep and their welfare. The shepherd is the means to ensure the end: the well-being of the flock. Sheep are first, shepherds last. John’s gospel portrays Jesus as the life-giving shepherd.

Vocations

The Fourth Sunday of Easter is also the World Day of Prayer for Vocations. The readings are very fitting for as we beg the Lord of the harvest and of the Church to send more labourers into his vast vineyards. As a model of religious leadership, Jesus shows us that love can be the only motivation for ministry, especially for pastoral ministry. He also shows us that there must be no exclusiveness on the part of the religious leader. If there are sheep outside the fold (even sheep excluded by the fold itself), the good shepherd must go fetch them. And they must be brought in, so that there will be one flock under one shepherd. The motivation for inclusion is love, not social justice, not ethical fairness, not mere tolerance, and certainly not political correctness or impressive statistics. Only love can draw the circle that includes everyone.

Shepherds have power over sheep. As we contemplate Jesus, the Good Shepherd, we call to mind everyone over whom we exercise authority — children, elderly parents, our coworkers and colleagues, people who ask us for help throughout the week, people who depend on us for material and spiritual needs. Whatever title we bear, the rod and staff we carry must be symbols not of oppression but of dedication. Today’s readings invite us to ask for forgiveness for the times we have not responded to those for whom we care, and ask for the grace to be good shepherds. We fix our eyes anew on the Good Shepherd who knows that other sheep not of this fold are not lost sheep, but his sheep.

One final thought on shepherding. Anthropologists tell us that between the hunting and the farming stages of cultural development shepherds stood as people who existed in both worlds and tied them together. For that reason, shepherds appear in ancient myths and sagas as a symbol for the divine unity of opposites. What the ancient pagans hinted at, Christian faith has brought into a crisp reality with Jesus Christ as the great reconciler. He is the Good Shepherd, who has come into the centre of every great conflict in order to establish beauty, unity and peace.

May it be ever so for each person who strives to be a good shepherd today, in the Church and in the world. As we enter those places of conflict and tribulation in our own times, may the Lord use us as his instruments to establish beauty, nobility, unity and peace?

Recent Sermons

Easter Sunday – The Resurrection

April 14, 2017

4th Sunday of Lent Year A – The Man Born Blind

March 27, 2017

3rd Sunday of Lent Year A – The Samaritan Woman at the Well

March 20, 2017